The Life of Pi

Posted on Mar 30, 2020 by Douglas Ross

Douglas Ross meets Eben Upton, founder of Raspberry Pi

As one of the youngest but fastest-evolving industries in the world, digital tech is catching us all off guard. In fact, we can no longer call it an industry. It permeates our lives and continues to develop in unforeseeable ways. All companies want to be a tech company, and nowhere more so than in Cambridge.

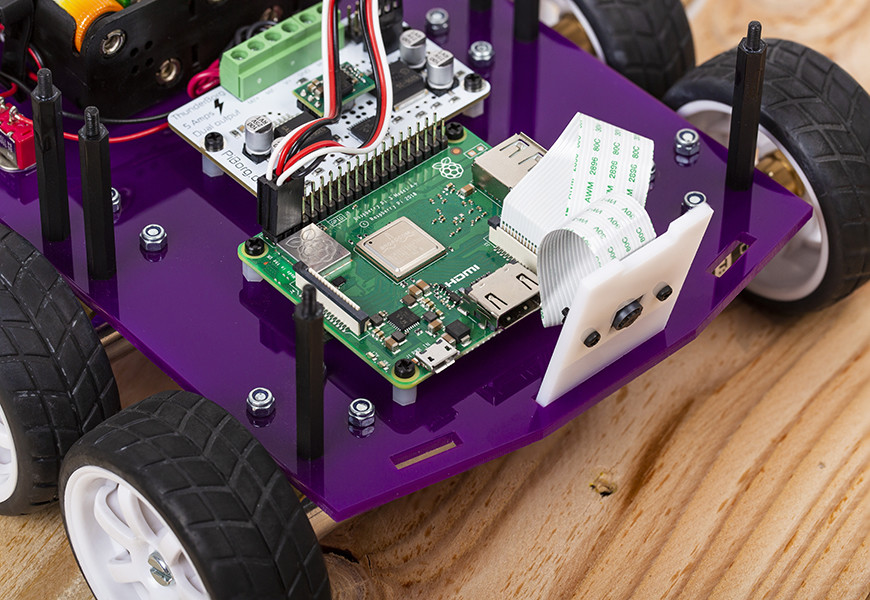

Just off Hills Road, a short walk from the Botanic Garden, the Raspberry Pi Foundation was created in 2008 by Eben Upton, who at the time was director of studies in Computer Science at St John’s College. Four years later, the foundation started producing lowcost, programmable minicomputers known as the Raspberry Pi, or Pi for short. A simple circuit board that fits in your hand and can be encased in a plastic shell, the Pi was originally constructed to be an introduction to the fundamentals of computer programming. So why did its release take several years?

“I think some of it is about the perils of distraction,” Eben admits. “There were periods in that window where therewere so many things to do in each of those areas of academia, business and tech that I found myself distracted. If you have a magpie mind, it’s very easy to never get anything done!”

Occupying these very overlapping sectors — academia, business and tech — helped Eben to identify how a non-profit could navigate the various challenges that occupy the terrain and come out with a viable solution to a major problem: tech literacy. But the popularity of the Pi was something that nobody in the foundation predicted.

Today, there have been over 25 million Raspberry Pi sold worldwide.

“We have customers buying tens of thousands of the minicomputers to network together as a training research platform,” Eben explains. “We designed this little machine to go into kids’ bedrooms; we didn’t imagine it would end up being used in high-performance computing research.”

The popularity of the Pi was something that nobody in the foundation predicted. Today, there have been over 25 million sold worldwide

The popularity of the Pi was something that nobody in the foundation predicted. Today, there have been over 25 million sold worldwide

The allure of the Raspberry Pi is the unforeseen manifestations that such a simple, programmable computer has produced. For Eben, one of the most interesting adoptions of the platform has been its recent use in high-performance research, as he explains.

“Most supercomputers are built of connected medium-performance machines, forming one high-performance machine. Raspberry Pi is nowhere near as powerful as the machines you put into a supercomputer, but if you take a bunch and network them together, you get a device that provides –in a scaled-down way – the development challenges for modern supercomputers. They for training and experimenting with new approaches.”

The Raspberry Pi’s origins are appropriately simple. Noting a marked decrease in student applications for computer science degrees at the university, Eben and others inCambridge identified a slow-burning crisis. Silicon Valley was racing ahead of Europe. The decreasing interest in technology in the UK augured a growing skills gap – the ramifications of which stretched far beyond Cambridge’s blushing limestone.

Global consulting firm Accenture estimated that the UK stands to lose £141.5 billion of the potential GDP growth that could come from the investment in (and adoption of) intelligent technologies. In Cambridge, decreasing applicant numbers in computer science degrees were a symptom.

We were becoming detached from technology’s tactility; our relationship with it slipping from active engagement to one of passive acceptance. Within just a decade or two of Steve Jobs dismantling and reassembling his first rudimentary computer, the magic of tinkering with tech was being lost.

“We talk about Raspberry Pi being a hypothesis test, really,” Eben reflects. “We had this hypothesis that, originally, we weren’t getting our people from formal education, but kids who were programming in their bedrooms. When the opportunity to do that went away, so did our applicant stream. We thought that if we could build a machine to house those properties, maybe our applicants would come back. And they did. Applicant numbers exceeded those in the late nineties and were up to approximately 1100 last year.”

Noting a marked decrease in student applications for computer science degrees at the university, Eben and others in Cambridge identified a slow-burning crisis

Noting a marked decrease in student applications for computer science degrees at the university, Eben and others in Cambridge identified a slow-burning crisis

Eben does not shy away from the role Raspberry Pi has played in bolstering Cambridge’s position as a tech hub, but he is aware that there are many working within the city to influence its placement as a global tech centre. Asked whether he sees tech ‘hubs’ as short-lived phenomena, he is less sure that any sort of technological innovation can be done just remotely. Instead, central hubs may be key to the growth of satellite contributors. While the engineering design of the Pi is done in Cambridge, the industrial design is outsourced to Bristol, the manufacturing of the plastic components to Dublin and the West Midlands, and the electronics manufactured in South Wales.

“It is important that you have clusters and that they can talk to each other. You probably can’t put all of these clusters in one place, and it’s a nice way in which a centralised area for tech can create employment in locations that may be more associated with older industry types,” Eben says.

Continuing to build on this tradition of the tactile importance of computer science, Raspberry Pi opened its first retail store in Cambridge’s Grand Arcade early this year. A physical space where visitors can play with the computer, the store has been a long-standing aspiration for many in the foundation. Its purpose is to talk to the people who use the computer and to learn from them directly.

For Eben, the past few months have confirmed the shop’s utility. “We’ve been running it for nearly three months now, and we are seeing people come in and decide to have a go – and also those who come in and decide not to, and we have the chance to ask them why. If we didn’t sell a single Raspberry Pi in the store, there would still be a lot of value to us in finding out why,” he explains.

The store’s design is segmented into six pods, with each one demonstrating different uses for the Raspberry Pi. In the few months it’s been open, the company has noted how strongly visitors respond to those applications of the platform that produce visible and physical results. This, and the scale of international interest in the computer, demonstrate that people have never, and possibly will never, lose their innate interest in the mechanics of digital tech. It may be up to those building tech to stay conscious of this need for active participation in and autonomy over it. At a time when the digital world increasingly plays with and inhabits the physical, keeping this tactility may be key for many products’ success in the future. The 8GB of storage in the original iPod wasn’t what made it so popular, but the effort put into its physical design. And the malleability of Android software continues to propel companies like Samsung forward.

For Eben, Cambridge continues to transform as a destination for some of the brightest minds in computer science and engineering. Some changes are plainly obvious and some more complex. For example: “We are working less with silicon, which is sad for me as a person from the silicon industry. On the other hand, we are working a lot more with software and a lot of hardware at the next level up.

We are also seeing a lot of changes in salaries. American companies have historically treated the UK as a mediumcost destination. The thirst for talent in Silicon Valley has become so extreme that people are now paying Silicon Valley salaries in Cambridge. This is great in that people are compensated, but it might be making start-up life a little harder. If you want good engineering talent of any kind, you have to compete. And then, of course, we have a new pivot to biotech …

“I came here in 1996 to study and I never envisaged being here 23 years later, but it’s such a compelling place. In terms of how people think and approach technology, there’s a different flavour to Cambridge than the U.S. The students make a big difference – having all of these bright young people crammed into a few square miles makes it fun and keeps you young,” he smiles.