Computer Love

Posted on Apr 1, 2020 by Cambridge Catalyst

Nicola Foley finds out more about the Centre for Computing History, Cambridge’s incredible archive of vintage tech

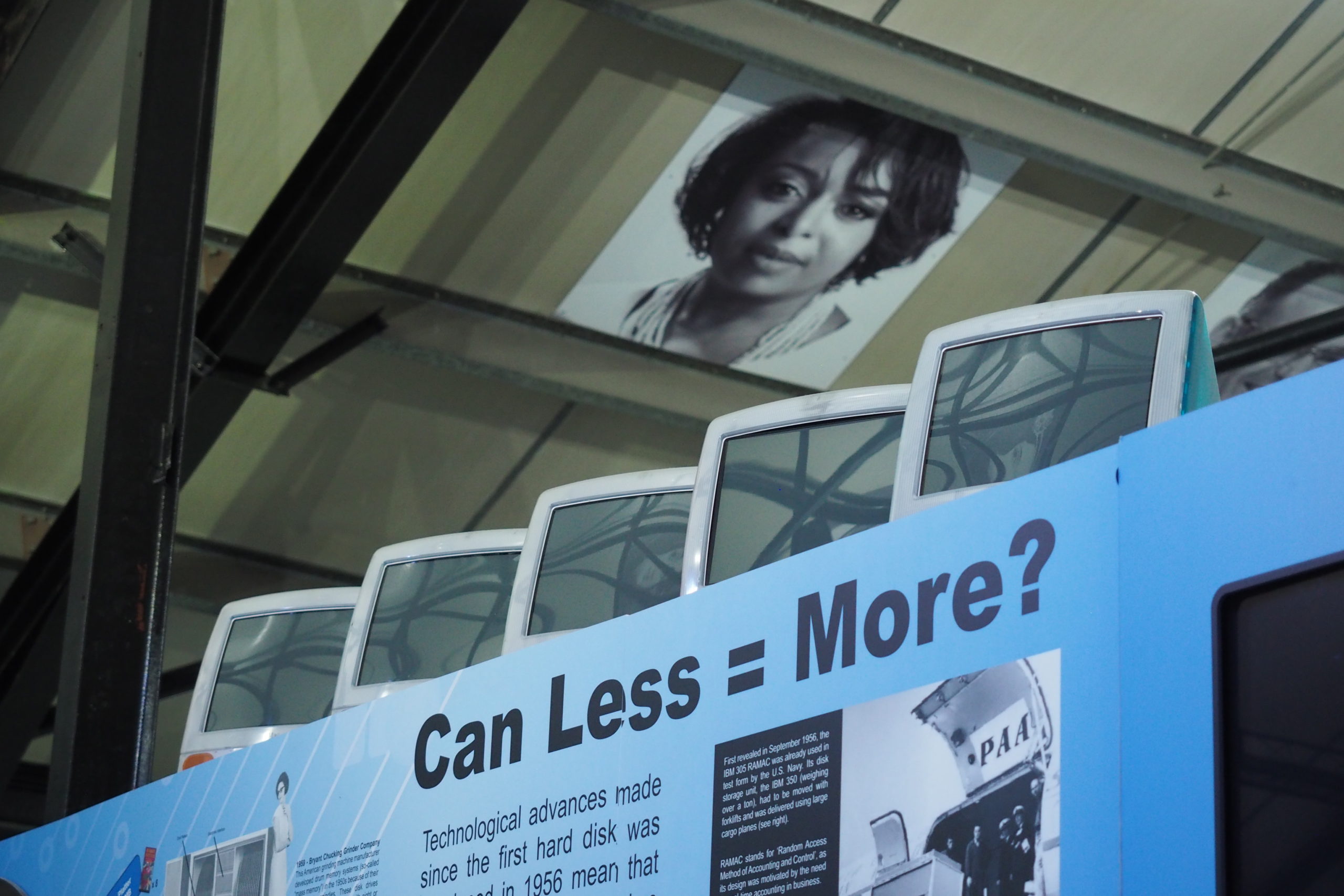

“If it’s something vaguely related to computers, we collect it,” grins Jason Fitzpatrick, founder of the Centre for Computing History, motioning around him at gaudy arcade cabinets, blinking servers and bulky monitors from bygone decades. With almost 40,000 artefacts to its name, this Coldham’s Road museum is home to one of the largest and most significant collections of vintage computers in the world, featuring everything from an Altair 8800 – which changed the game for personal computing back in the 1970s – to a PlayStation 4 Pro, via countless mobile phones, calculators, some 12,000 games, 10,000 computer-related magazines and approximately 6,000 books.

The story of this awesome archive of techy paraphernalia began with Jason’s modest personal collection, some of which was stored at his web design company’s office in Haverhill. “I had a Spectrum up on a shelf of BBC Micros, as artwork really. It didn’t matter who came in, everybody pointed them out, and we’d waste the first half an hour of meetings reminiscing”, he remembers. “Even younger people that didn’t use it remembered it from their parents having them, and it just seemed to me that everybody had an interest – so, I thought, well maybe there’s an exhibition we could do?”

The story of this awesome archive of techy paraphernalia began with Jason’s modest personal collection, some of which was stored at his web design company’s office in Haverhill. “I had a Spectrum up on a shelf of BBC Micros, as artwork really. It didn’t matter who came in, everybody pointed them out, and we’d waste the first half an hour of meetings reminiscing”, he remembers. “Even younger people that didn’t use it remembered it from their parents having them, and it just seemed to me that everybody had an interest – so, I thought, well maybe there’s an exhibition we could do?”

Jason moved into a larger building with space to showcase the collection, building a website to get the word out – and rather unexpectedly, “people just kept showing up with more stuff!” he laughs, shaking his head. Soon enough, the burgeoning collection attracted the attention of Neil Davidson, co-founder of Redgate Software, who told Jason he ought to consider moving the museum to Cambridge and offered to make introductions to help secure the necessary funding.

“He was involved in Cambridge Network at the time, so he introduced us to some companies, and we managed to get some sponsorship money together… We got Arm, Redgate, Microsoft Research, RealVNC to all put in some money”, recalls Jason. “We opened up day one with some tables in a big warehouse with nothing else in it, and invited people to come in and see the stuff for four quid.”

Today, much has changed, not least the size of the collection, which grows larger all the time thanks to the almost daily donations which arrive at the centre.

“It was based around my collection originally – which I thought was huge, and for a private collection it probably was, stupidly so,” says Jason. “But actually, that got dwarfed by what the general public gave, and industry gave, and the military gave.”

When somebody comes in with their computer, they’re donating a little bit of their history, but the machine’s not necessarily it

When somebody comes in with their computer, they’re donating a little bit of their history, but the machine’s not necessarily it

“There’s an interesting thing about this stuff”, he continues. “When somebody comes in with their computer, they’re donating a little bit of their history, but the machine’s not necessarily it. People say things like, ‘oh, this is a Mac that I did my dissertation on, it’s lovely to think it’s going to be in the museum – you will look after it won’t you?’, like they’ve just given their child! It’s so personal, the term personal computer is far more personal than anybody ever thought it would be. People are handing over a part of their life, so that makes it really nice for us when people hand over a bit of their life, a bit of their own history.”

The Information Age

But while many of us feel a personal attachment towards our computers, if any industry values newness, it’s computing. In a market where today’s hi-tech wonders are tomorrow’s scrap material and the latest, new and shiny model is always just around the corner, why bother to preserve?

“Because nothing has changed who we are and the way we live the way that computers have,” says Jason simply. “Just look at it all, it, everything has changed: there isn’t a walk of life that isn’t affected by it. Our lives our completely intertwined with technology: we are a part of it as much as it’s a part of us.”

A part of CCH’s mission, explains Jason, is chronicling the story of the Information Age; examining the social and cultural impact of the developments in personal computing. There’s a generation of ‘digital natives’ growing up now who have little knowledge of a time pre-internet and pre-personal computing; and considering how far-reaching the effects of this technology have been on our world, those at the centre believe it’s a story that deserves telling.

As well as looking back on our digital history, Jason stresses that the centre has an important role to fulfil in educating future generations about the impact – and potential dangers – of the technology which now infiltrates every aspect of our lives.

“In terms of the area we concentrate on, it’s really the personal computer evolution. There were machines way before the mid-70s, big machines that filled entire rooms, but they didn’t touch upon people’s lives that much… Those computers weren’t powerful, so the things that you could make them do didn’t have much impact. Now we have computers that dominate our lives. The things we can make them do need to be thought about,” he explains. “It’s now not just about “can we?”, it’s about “should we?” It’s a major issue. We get school groups in and we talk about it; there are implications now. It’s very much about the social impact of it all.”

“In terms of the area we concentrate on, it’s really the personal computer evolution. There were machines way before the mid-70s, big machines that filled entire rooms, but they didn’t touch upon people’s lives that much… Those computers weren’t powerful, so the things that you could make them do didn’t have much impact. Now we have computers that dominate our lives. The things we can make them do need to be thought about,” he explains. “It’s now not just about “can we?”, it’s about “should we?” It’s a major issue. We get school groups in and we talk about it; there are implications now. It’s very much about the social impact of it all.”

“These big companies, they know everything about you. What does that mean? It can get really deep, and we don’t want to scare anyone” he adds. “But we’ve seen a few things go a bit wrong with the elections and things like that and that’s just the tip of the iceberg. But it’s good just to be aware of it, for kids to understand that actually there is a side to this that we’ve probably already messed up a little bit, and that they’re going to need to unpick this.”

Hollywood Calls

When a collection reaches the scale and prestige of CCH’s, it naturally attracts interest – sometimes from unexpected quarters. “We do a lot of work with the TV and film industry, either supplying equipment or consulting,” says Jason, reeling off a list of some of the huge Hollywood films that items from the collection have recently made star turns in.

When Steven Spielberg set about making Ernest Cline’s epic dystopian Ready Player One into a blockbuster movie, it was the Centre for Computing History that was sought out to provide era-accurate tech, and the same for Charlie Brooker’s recent ‘choose your own adventure’ Netflix smash Bandersnatch.

We do a lot of work with the TV and film industry, either supplying equipment or consulting

We do a lot of work with the TV and film industry, either supplying equipment or consulting

“That was huge – fun, but hard”, recalls Jason. “It’s nice doing it for Netflix because they have a lot of money, so a lot of these things are like ‘oh well we’re on a budget’ – but with this, within reason, there wasn’t a budget and it was like ‘just make this flipping perfect’ – and we did, it took months and months.”

Jason and his team supplied and set-up all of the tech for the show’s fictional game studio Tuckersoft, taking over an entire floor of the One Croydon building and filling it with retro computers and gadgets.

“I built all the computers there and everything. Every computer; everything that had a plug on it was me!” he laughs. “Charlie Brooker loves the techy stuff to death, and he mentioned a few things that he really wanted to see in there, like a Kempston joystick and an original Spectrum… When it came to the hero sets, every detail was in it, because Charlie is all about that. The character Stefan had a TRS-80 and a Spectrum and we had cables that went there and it was all completely real, and fortunately – because computer people are a bunch of muppets that love to tear you apart – I don’t think anybody tore any of it apart!”

While the work can get slightly tedious, the endless tinkering and research that goes into making something completely historically accurate and which actually works, is a process that Jason relishes.

“The thing is that I tell people is that back in 1975 I didn’t have a computer – I wanted a computer – I cut a hole out of a cardboard box and I made one and I made a keyboard and stuff and I pretended as a kid…. I’m now nearly 50 and I’m still doing the same thing. I’m doing it with real machines but it’s still pretend, so nothing’s really changed. And it’s brilliant!”

A Cambridge Story

Cambridge is a fitting location for this incredible archive, given its deep links with the history of computing. When tea shop chain J. Lyons & Co. became the first business to implement electronic computing in 1951, it did so using a variant of the Cambridge University EDSAC machine – the Lyons Electronic Office (LEO) – to digitise its workplace, thereby kickstarting a revolution in commercial computing.

“It’s an amazing story”, smiles Jason. “Lyons went to the University of Cambridge and said ‘this computer you’re building for research – we think we could use it for business’, and nobody else had thought about using a computer for business at that time! This tea shop effectively would develop a computer to run their business, and then later on it’s just the way it is for everyone. It’s a British story, it’s a Cambridge story, and we’re doing a lot of work to get that story out there.”

Cambridge was also home to Sinclair Research, which in 1980 brought the ZX80 to market with a price tag of under £100, making it the first truly affordable personal computer. It quickly became the top selling home computer in the UK, with the even more affordable ZX81 attracting yet more customers. Sinclair’s position in the canon of personal computing was cemented in 1982 with the release of the iconic ZX Spectrum, which would go on to sell more than five million units, earn company founder Clive Sinclair a knighthood and spark an interest in programming in a generation of young people. Affectionately known to its fans as the ‘Speccy’, the legend and legacy of this 8-bit personal computer lives on today: in fact, recent weeks have seen the release of the Kickstarter funded Spectrum Next, a brand-new machine that’s fully compatible with the original, with added improvements and expansions.

Cambridge was also home to Sinclair Research, which in 1980 brought the ZX80 to market with a price tag of under £100, making it the first truly affordable personal computer. It quickly became the top selling home computer in the UK, with the even more affordable ZX81 attracting yet more customers. Sinclair’s position in the canon of personal computing was cemented in 1982 with the release of the iconic ZX Spectrum, which would go on to sell more than five million units, earn company founder Clive Sinclair a knighthood and spark an interest in programming in a generation of young people. Affectionately known to its fans as the ‘Speccy’, the legend and legacy of this 8-bit personal computer lives on today: in fact, recent weeks have seen the release of the Kickstarter funded Spectrum Next, a brand-new machine that’s fully compatible with the original, with added improvements and expansions.

The centre was involved in helping to bring the Next into production, and houses the original prototype of the Sinclair Spectrum in its collection – which is one of Jason’s most prized exhibits.

“I think it’s fair to say it was part of the kickstart of the entire British games industry” he says. “A lot of people wrote the start of bedroom coding on the Spectrum, and we have the very birth of it: a circuit board, it’s pure electronics and software”.

Game On

These early pioneers in personal computing paved the way for Cambridge’s current crop of successful video games developers, which ranges from behemoths like Jagex to quirky indie studios like the excellently named Utopian World of Sandwiches.

It’s a scene which the centre is proud to be involved with, hosting expos that offer guests a chance to see a showcase of the city’s booming gaming landscape alongside gems from its past, as well as allowing studios to play-test their latest launches with the public at gaming nights.

“There’s a really thriving scene in Cambridge, and I think it’s historical and linked to the whole Cambridge Phenomenon thing: people are inspired by other people. This whole thing’s about people, and I love it; it’s so creative – all these people coming up with ideas and all this cross-fertilisation it’s brilliant.”

This whole thing’s about people, and I love it; it’s so creative – all these people coming up with ideas and all this cross-fertilisation

This whole thing’s about people, and I love it; it’s so creative – all these people coming up with ideas and all this cross-fertilisation

As well as embedding itself within the latest developments, as always CCH has an eye on the past; in this case preserving video games for future generations – a technically complex process which has formed an important part of the centre’s work for the past 12 years. For the centre, the idea of video game preservation means exactly that: preserving these games, from which so much can be gleaned about the technological and social context in which they were made, as they were originally; from the hardware to the associated ephemera like manuals and packaging. With more than 12,000 games in the collection and more arriving every day, it’s no small task.

“The video game preservation is our real push for this year; it’s really, really important to us”, says Jason. “We need a ton of help to do it though, otherwise it’s just going to take a thousand years. And we can’t do it on our own, we need companies to support us and to say: ‘here’s our stuff, this is the history of this game, how it was developed and why it was developed.’ We want to talk to people, we want to interview them, but they need to come forward because we can’t go out there, we haven’t got a research team unfortunately. Companies can give us a research team if they want and sponsor us. It’s not solely Cambridge’s history that we’re preserving, but obviously there’s a lot of it coming forward – it’s bigger than that. And it would be really nice if we could get Cambridge businesses to help us do that. A lot of them doing a little bit – nobody would feel the pinch”.

There’s a really thriving scene in Cambridge, and I think it’s historical and linked to the whole Cambridge Phenomenon thing: people are inspired by other people

There’s a really thriving scene in Cambridge, and I think it’s historical and linked to the whole Cambridge Phenomenon thing: people are inspired by other people

The Next Chapter

As well as continuing in its important preservation work, hosting events and exhibitions and continuing to educate old and young about our history and relationship with technology, Jason is clear on what he hopes the future holds for the Centre of Computing History.

“To be a massive shiny building in the middle of Cambridge!” he grins. “We own this place now and we love it, but it’s not the place, it’s the place that gets us to the place… We’ve always been quite nimble as an organisation, so we can take advantage of things that happen. If, say, they develop a museums quarter or whatever or something in Cambridge – we now have one and a half million pounds worth of asset that says: ‘okay, we could sell this and move into this place and put that money into there.’ We’re in an amazing position for a museum that is this young… We represent Cambridge’s history of computing, and this doesn’t. While I’m massively proud of it, you’ve got to look at it from a point of view that other countries would possibly expect Cambridge to have something that was pretty amazing. I mean, there’s a computer history museum in Silicon Valley and it’s got an amazing building, and that would be amazing.”

“At the end of the day you’re going to die, and what have you got to show for it? I don’t know why that I feel like I need to do something that does that will live beyond me. Hopefully,” he concludes. “And yeah, and this is that – but it’s not the thing yet, we’re not there yet, so we need to get this big shiny building…”